Battlestar Galactica: a guide for watching the show

Table of Contents

- 1. Battlestar Galactica Viewing Order

- 2. Further reading

- 3. The story so far

- 4. Episode reviews

- 4.1. Season 02 Episode 14: Black Market

- 4.2. Season 03 Episode 07: A Measure of Salvation

- 4.3. Season 03 Episode 08: Hero

- 4.4. Season 03 Episode 09: Unfinished Business

- 4.5. Season 03 Episode 10: The Passage

- 4.6. Season 03 Episode 14: The Woman King

- 4.7. Season 03 Episode 18: The Son Also Rises

- 4.8. Caprica Episode 18

- 4.9. Season 03 Episode 20: Crossroads

- 4.10. Season 04 Episode 03: The Ties That Bind

- 4.11. Season 04 Episode 04: Escape Velocity

- 4.12. Season 04 Episode 07: Guess What's Coming To Dinner

- 4.13. Season 04 Episode 04: Sine Qua Non

- 4.14. Season 04 Episode 14: Blood On The Scales

- 4.15. The Plan

- 4.16. Season 04 Episode 16: Deadlock

- 4.17. Season 04: Battlestar Galactica Finale (S04E17-18-19-20)

- 4.18. Bloopers

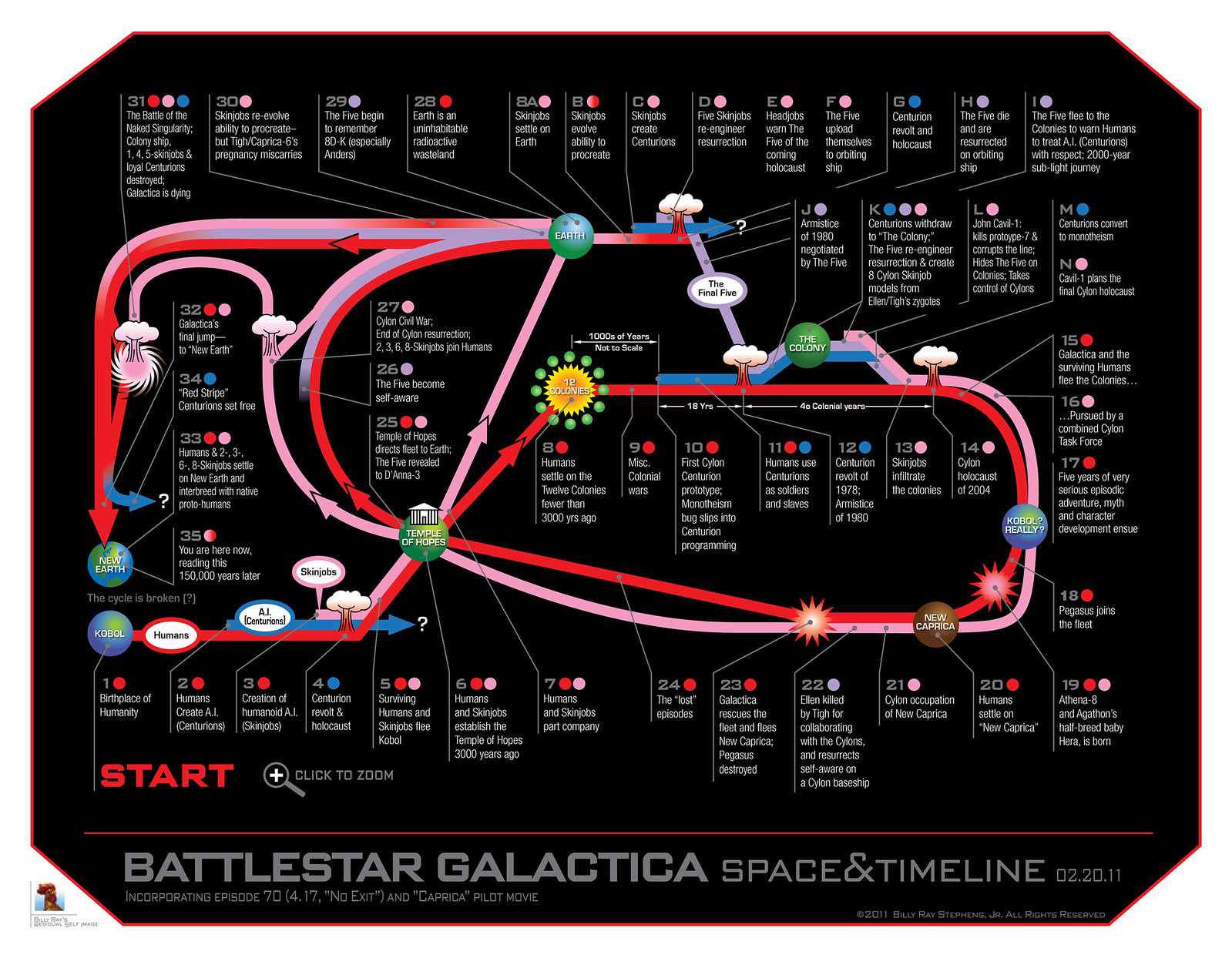

- 5. Timeline

Battlestar Galactica stayed with me for the first part of 2021. It is a great work of art and probably my favorite tv show. In addition to that Battlestar Galactica was displayed in a time where internet and particularly the web was a very different medium from what came to be. The web was ripe with blogposts related to this show, blog wars on fan fictions and some honest reddit reviews. I am trying with this guide to give future viewers a sense of what it means when culture is not constrained into the cage of user hostile technologies such as streaming servicies and walled social media.

1 Battlestar Galactica Viewing Order

The ultimate viewing order for Battlestar Galactica!

With so many off-shoots, extended episodes, webisodes, one-off movies and weird bits and pieces it's very hard for a new Battlestar Galactica fan to know exactly what order to watch everything in.

That's why, with the help of the kind folks at the Home Theater Forum, I decided to piece together a recommended viewing order for the entire series. But not just that, I've put together information on which versions of episodes you should watch and where you can find them, too. This really is the ultimate guide! (At least, it should be.)

I hope you find it useful, and if you do think I've missed something, please leave a comment and let me know!

Thanks to Johnny Walker for giving the inspiration for the watching guide but also most of this post (http://thunderpeel2001.blogspot.com/2010/02/battlestar-galactica-viewing-order.html).

1.1 Blood and Chrome

This was potentially a whole new show at one stage, but it appears to be now just a stand-alone TV movie. The story follows the exploits of a young William Adama during the First Cylon War, and is considered a sequel to Caprica and a prequel to Battlestar Galactica.

After disappearing off the radar for a long time (possibly indicating that it wasn't up to the standards set by BSG), the story was finally been release for viewing on Machninima.com in 10 episodes. Then it was released on DVD/Bluray as a movie in a rated and unrated form.

I've been told there are no BSG spoilers, so you can watch this anytime you want. I decided to watch this in the beginning to get a sense of the universe of the story and understand if I wanted to start watching the whole show. It gives you a taste of a lot of the elements at the core of the show but the story is a little bit predictable and also told in the rest of the show for the most part. That's why I think it is most enjoyable to watch this movie before embarking on the whole journey.

1.2 The Miniseries

- Night 1

- Night 2

1.3 Season 1

- 1.01 33

- 1.02 Water

- 1.03 Bastille Day

- 1.04 Act of Contrition

- 1.05 You Can't Go Home Again

- 1.06 Litmus

- 1.07 Six Degrees of Separation

- 1.08 Flesh and Bone

- 1.09 Tigh Me Up, Tigh Me Down

- 1.10 The Hand of God

- 1.11 Colonial Day

- 1.12 Kobol's Last Gleaming, Part I

- 1.13 Kobol's Last Gleaming, Part II

1.4 Season 2

- 2.01 Scattered

- 2.02 Valley of Darkness

- 2.03 Fragged

- 2.04 Resistance

- 2.05 The Farm

- 2.06 Home, Part I

- 2.07 Home, Part II

- 2.08 Final Cut

- 2.09 Flight of the Phoenix

- 2.10 Pegasus (56 minute extended version)

- 2.11 Resurrection Ship, Part I

- 2.12 Resurrection Ship, Part II

- 2.13 Epiphanies

- 2.14 Black Market

- 2.15 Scar

- 2.16 Sacrifice

- 2.17 The Captain's Hand

1.4.1 Razor

The 101 minute extended version - not the 81 minute broadcast version movie. If you have this on DVD or Bluray, you have the extended version.

Important note: This was originally broadcast just before Season 4, but chronologically it fits here, telling more of the Pegasus's story. Some people argue it's better to watch after Season 3, as originally broadcast, but it makes most sense to watch it here. We can say that chronologically all of the events in the movie fits here, but thematically it fits the beginning of series 04 (on some forums Razor is referred as S04 E01-02). On Jammer's review we can read regarding the events on the Pegasus aired originally at the end of S03

Still, on a series that has always benefited from the fact that we never know exactly what lies around the next corner, all of this feels slightly redundant.

The reason that the placement of Razor is a hotly contested issue among BSG fans is because of a bit of dialogue at the very end (in the last 10 minutes) which sets the tone for Season 4 (barely even a spoiler). Everything else in this TV movie is not a spoiler.

So why place it here, and not where it was originally broadcast, if there's any sort of issue? Because, chronologically, the story is set here, and by the time you reach the end of Season 3, the story on the Pegasus will feel like ancient history. Indeed, that was the complaint echoed around the internet from fans after Razor originally aired – it had nothing to do with what was going on in the story at that time.

As a result of this, most fans agree it's better to watch Razor here. In doing so, you'll appreciate the story more and it will have greater emotionally resonance. In short: I highly recommend that you follow my advice and watch it here.

There is one small caveat, however: In order to deal with the above dialogue issue, and so not to unintentionally alter the tone of Season 3, I have two, very specific instructions that I recommend that you follow for your absolute optimum enjoyment.

I will try not to spoil anything with these instructions, so pay attention. You need to press MUTE on your TV (and/or turn off any subtitles) in the following moments. These moments occur in the last 10 minutes of the story, so you can relax and enjoy the first 90 mins before you need to worry.

Personally I stopped viewing at -07:13 because the end is predictable and doesn't contain any major insight for the story except spoilers. If you really want to finish the movie, press MUTE when:

- The hybrid touches Shaw. (You can unmute as soon as the hybrid lets go.). Then, shortly afterwards:

- When Red One contacts Pegasus. (You will literally hear the dialogue, "This is Red One come in" and see Pegasus respond – mute before Red One can give their message to Pegasus.) You can unmute when you see Red One on your screen – actually before that, but there's no other visual clue I can give you.

- When Starbuck is talking to Lee, mute after Lee says, "Well, ever think you might deserve it?". You can unmute when she turns to leave.

That's it! That's all you have to worry about. A couple of very small moments, and even if you don't unmute it, it's not a huge spoiler, it just unintentionally alters the tone of Season 3 if you don't, so do try your best to follow my instructions.

1.4.2 Optional: Razor Flashbacks

Note: This was billed as a "seven episode web series", but really they are just deleted scenes from the shorter broadcast version of Razor. In fact, most of these scenes are now reintegrated into the extended version of Razor (the one on DVD and Bluray), making what's left even more unessential.

They are mentioned here only for the sake of completeness, and because they're often a source of confusion. Don't worry, they are far from necessary. The only "episodes" not reintegrated are 1, 2 and some parts of 7, so they're the only ones to note.

All 7 of these "episodes" were originally released online before Razor was broadcast, and I'd recommend watching 1 and 2 beforehand, and 7 afterwards. They don't really add much to the story, though.

1.4.3 Rest of season 2

- 2.18 Downloaded

- 2.19 Lay Down Your Burdens, Part I

- 2.20 Lay Down Your Burdens, Part II

1.5 The Resistance

A 10 episode web-based series bridging seasons 2 and 3. (25 mins.) This should be included on your DVDs/Blurays.

1.6 Season 3

- 3.01 Occupation

- 3.02 Precipice

- 3.03 Exodus, Part I

- 3.04 Exodus, Part II

- 3.05 Collaborators

- 3.06 Torn

- 3.07 A Measure of Salvation

- 3.08 Hero

- 3.09 Unfinished Business (70 minute extended version - Note: Not included on Region 2 DVDs, but is included on all Blu-ray releases.)

- 3.10 The Passage

- 3.11 The Eye of Jupiter

- 3.12 Rapture

- 3.13 Taking a Break From All Your Worries

- 3.14 The Woman King

- 3.15 A Day in the Life

- 3.16 Dirty Hands

- 3.17 Maelstrom

1.6.1 Caprica

An entire TV series set 58 years before the events of Battlestar Galactica, and revealing the events surrounding the creation of the Cylons. (Although it's worth noting that you don't have to have seen BSG to watch Caprica… and some people have decided to watch this series first, even though it was produced after BSG had finished.) Battlestar Galactica is not a show to should be binge watched. The plot being easy to follow and the almost complete absence of fillers makes it very difficult to stop at the end of the episode and not diving into the next. It doesn't help that even if the story has many intricacies it takes place in just a handful of months.

At the end of episode 3.18 I got the feeling that I was hurrying. While I was in excitement every day to start a new episode I noticed that I was overlooking some shoots such as the majestic CGI of the ship and while badly forestalling important moments of the episodes. For this reason I decided to press pause while diverting my attention to "Caprica", knowing that it shouldn't contain major spoilers for the rest of Battlestar Galactica.

Having known this, S03E17 is an ideal point to interrupt season 3 because we have one major event that shakes the balance of the crew and after this episode we will begin a new story arc that I don't think will introduce new plot elements but will deal with a lot of steaming elements of interest for the entire fleet. Without knowing the future of the story I believe that we are at a stable point in which we don't have vision of major unfolding and the big questions of the show have been lingering for a while.

- 1.01 Pilot

- 1.02 Rebirth

- 1.03 Reins of a Waterfall

- 1.04 Gravedancing

- 1.05 There Is Another Sky

- 1.06 Know Thy Enemy

- 1.07 The Imperfections of Memory

- 1.08 Ghosts in the Machine

- 1.09 End of the Line

- 1.10 Unvanquished

- 1.11 Retribution

- 1.12 Things We Lock Away

- 1.13 False Labor

- 1.14 Blowback

- 1.15 The Dirteaters

- 1.16 The Heavens Will Rise

- 1.17 Here Be Dragons

- 1.18 Apotheosis

1.6.2 Rest of season 3

- 3.18 The Son Also Rises

- 3.19 Crossroads, Part I

- 3.20 Crossroads, Part II

1.7 Razor

This is where Razor was originally broadcast. Remember the last 07 minutes where I told you to MUTE two small moments? Well, guess what, now is when you get to go back and hear what was said. Watch the last 10 minutes of Razor here.

1.8 Season 4

- 4.01 He That Believeth In Me

- 4.02 Six of One

- 4.03 The Ties That Bind

- 4.04 Escape Velocity

- 4.05 The Road Less Traveled

- 4.06 Faith

- 4.07 Guess What's Coming to Dinner?

- 4.08 Sine Qua Non

- 4.09 The Hub

- 4.10 Revelations

- 4.11 Sometimes a Great Notion

1.8.1 The Face of the Enemy

A 10 episode web-based series (although it plays together like an intense mini-episode). (36 mins.)

These episodes have not been included on any DVD or Blu-ray releases, except for the Japanese Blu-ray release of Season 4. A real pain.

They are not presently available anywhere else in the world to my knowledge, but I highly recommended you do your best to find them. Not only were they hugely enjoyable, but they explain a few important things that set up the next episode.

1.8.2 Rest of season 4

- 4.12 A Disquiet Follows My Soul (53 minute extended version)

- 4.13 The Oath

- 4.14 Blood on the Scales

- 4.15 No Exit

1.8.3 The Plan (DVD/Bluray movie)

A stand-alone movie that shows (approximately) the first two seasons from the Cylons' perspective. (You finally get to see "The Plan", mentioned all those times in the opening sequence!) Although The Plan was originally released after the show had finished, it is generally agreed that it should be watched here, so that everything is all tied up when you do reach the end.

1.8.4 Finale

- 4.16 Deadlock

- 4.17 Someone to Watch Over Me

- 4.18 Islanded In a Stream of Stars (62 minute extended version - only on BluRay releases and Region 1 DVDs)

- 4.19 Daybreak (150 minute extended version - only on BluRay releases and Region 1 DVDs)

2 Further reading

Well not quite "reading", but if you're a fan you may enjoy the following:

Ron Moore's Battlestar Galactica podcast is nothing short of incredible, and highly recommended for fans and wannabe TV writers. As he goes through each episode, I believe you can watch the show and listen to his comments without fear of spoilers.

You can read the show's original "Bible", contains of course major spoilers.

3 The story so far

Battlestar Galactica: The Story So Far is a special program aired on the Sci Fi Channel that summarizes the first two seasons of the Re-imagined Series. The special was intended to attract new viewers and offers no new content for frequent viewers of the series. [1]

On the evening of August 13, 2006, NBC affiliates on the U.S. West Coast broadcast the special following the Cincinnati-Washington NFL football game. The program was aired repeatedly on the Sci-Fi Channel in August/September 2006 prior to the Season 3 premiere.

Narrated by actress Mary McDonnell (voicing the narration in her character of Laura Roslin), The Story So Far ignores several supporting and significant story arcs and character developments in the interest of the program's limited 43 minute air time.

Significant information missing from the special program include:

- The trials of Helo while marooned on Caprica in Season 1

- The arrival of the battlestar Pegasus and Adama's conflict with its commander, Admiral Cain

- The relationship between Galen Tyrol and Sharon Valerii

- The presidential coup that leads to the arrest of Laura Roslin, the declaration of martial law and the temporary splitting of the Fleet.

- Any reference to Billy Keikeya, a central supporting character in Season 1

The feature provides two possible answers to questions posed in the series:

- The civilians who were left behind with Helo on Caprica, died due to radiation poisoning.

- Crewmembers who suspect Boomer of being a Cylon wrote the word on her mirror in "Six Degrees of Separation".

Areas that attempt to plot significant events of the show include a recap of the Miniseries in the program's first twenty minutes, a synopsis of the first season by the half-hour mark, and generally concise information on Season 2. Several scenes are generally shuffled out of their aired timeline to explain important relationships.

I haven't see this movie and honestly I don't look forward to it.

4 Episode reviews

Here I gathered some reviews on the most significant episodes of Battlestar Galactica. Some of the reviews were written by me.

4.1 Season 02 Episode 14: Black Market

It's very out of character for Lee. I mean, even if we were to infer that all that happened since his brush with Zarek on the Astral Queen in S1 chipped away not only at his will to live, but also his principles, we end on Lee willing to kill the ring leader and go right back to his old self in the next few episodes, making Black Market an inconsistency in an otherwise well fleshed out charakterization. The same goes for his out-of-nowhere romantic interest with a random woman on Cloud 9 and a hitherto unknown past romance. It interrupts already existing plot threads, has no setup, is played like it's been going on for a while, and is dropped by the end of the episode.

There's also the fact that the message, "the fleet needs the black market" doesn't work in the limited economy the series presents us with. If the shipment's late, there's no benefit in having people sell illegal stockpiles for absurd prices that were grifted off earlier shipments. The black market isn't in possession of alternative means of supply, and can't conjure medicine out of thin air this far into the journey. It would make some sense when talking strictly about luxury items and their positive impact on morale, but the episode is specifically about medicine, and if anyone should have stockpiles of that, it's Official sources.

Worse still, the black market disrupts the command structure by murdering officers and therefore actively undermines the fleet's fighting force, which is suicidal. A Mafia getting cocky enough to kill military officials works only in circumstances in which that isn't equivalent to potentially killing yourself and all your customers. This might've worked on New Caprica, or in a Flashback to the colonies, but not on a resource-stricken fleet that's actively engaged by cylon forces. It's telling that letting Lee live is a classic villain mistake, and played as such- and the logical choice in-universe, a clear indication that the Mafia shouldn't be out murdering military staff in the first place.

This makes everyone look kind of incompetent or thoughtless- Fisk could've met the Black Market boss, have a Marine detachment arrest them, present Adama with evidence of their deeds, have them court martialled, and bag more than he bought by simply lying about how he knew. And the fleet would've likely been safer, not to mention that might've been a more interesting plot line than "standard" Mafia affairs. And since it's promptly forgotten, with Lee being reversed to normal, you actually have a more coherent S2 by skipping Black Market than watching it.

Tl;dr- Black Market fails not because it's bad television by itself. It's well acted, well paced and has a poignient finish- just delivered in a way that doesn't work due to unique circumstances within BSG. It fails because its plot structure doesn't work within its the universe and has to change a major character to simply exist, development of which doesn't translate to further episodes. It is superfluous, as if a good episode of a different show was mistakenly aired as part pf BSG.

Right at the start of the commentary RDM says that he dislikes this episode. And he takes full responsibility for it being a bad episode.

And then throughout the rest of the commentary he talks about how much he hated the whole episode.

He's an excerpt from the beginning of the commentary…

And today's podcast we're gonna be do something a little bit different, actually, than the norm. We're going to be talking about an episode that I don't particularly like (Chuckles) and discussing maybe the reasons why it doesn't work and the problems that I think are inherent in this particular episode. I think I should also make it clear from the outset that the criticisms and implied criticisms of this episode really should not be laid at the doorstep of the production team, or the cast, or crew, or the writing staff, or anybody else. It's really my responsibility as head writer and one of the executive producers. The decisions that led to this episode being something that I'm not as enamored with really can all be tracked back to decisions that I made at various stages in the creative process. So this is really a- a podcast devoted to self-examination and self-criticism, more than anything else, and going through why this particular episode doesn't seem like it fits as well within the- the pantheon of what we've established.

And the end…

So there you have it. There's "Black Market". There's my digging through the guts of a show and telling you all the reasons why it doesn't work. So I hope you're happy now. (feigned sadness) I hope you're happy that you've broken me down to this level. (resumes normal voice) Next week, I can tell you we have a great episode. "Scar" will be something I think we're all very proud of and very excited about and I look forward- forward- I'm looking forward to going through the podcast commentary track on that with you. Thank you and goodnight.

4.2 Season 03 Episode 07: A Measure of Salvation

I also want to address this from another angle: that sparing the Cylons is one of the most important things that the Human race could do.

The central theme of the series is religious. It's that, throughout every season, it should be obvious that it's not just human versus cylons, that there is a higher power orchestrating everything.. observing.. judging.

Ultimately the meta efforts of humans and cylons to survive or fight are meaningless. The outcome is dictated by the higher power.

Under this assumption, the show becomes proving that humans deserve salvation. This episode is aptly named "a measure of salvation" referring to the act of Helo that probably saved the human race in the eyes of this higher power. If it sounds silly that one human can grant salvation for his entire race, there's a dominant religion today based around that idea.

Sure, wiping out the Cylons might help the human race survive in the short term. But…

"It is not enough to merely survive, one has to be worthy of survival" -Adama

4.3 Season 03 Episode 08: Hero

This is regarded as one of the worst episode of BSG along with "Black Market" and "The Woman King". Discussion is delayed until E14.

Personally I don't think that Adama is portrayed in a bad light because it is obvious that the Cylon attack was in preparation way before the trespassing of the red line. Laura says that herself: "Simple solutions only gives you the semblance of control but it is stupid to believe that complex situations stems from a singular episode" (not a literal quote).

4.4 Season 03 Episode 09: Unfinished Business

During Starbuck's fight with Lee Adama, once it becomes obvious that she stands a good chance of losing she quickly begins using arm locks and kicks to gain an advantage. Once knocked to the ground, she sweeps Adama's legs out from under him. This is reminiscent of Starbuck's expressed attitude in "Scar" that war is not bound by ideas of honor or fair play.

There's a small revelation that happens this episode (that you can only see in the extended cut) that shows how Tigh and Starbuck became friendlier to one another in the year that passed. They share their first (friendly) drink together and Tigh offers a small bit of advice about Kara's choice between Anders and Lee. It's a shame this scene was cut from the aired version because I think it goes a long way to showing that Kara wasn't as heartless in her decision to marry Sam after having just confessed her love for Lee.

The boxing setup is a little gimmicky, but I think BSG made it work. The little additions like Doc Cottle shadowboxing during an early match, and Roslin having a background in boxing due to her father, filled out the episode and made it work for me, despite the “fight out your feelings” premise. It was also interesting to see a completely different New Caprica— blue skies and hope. (And was that Roslin and Adama getting high?)

Bill’s speech was pretty intense for a "fun" event. It essentially reaffirmed his authority, and drew new boundaries on the expectations— basically, “you all aren’t civilians anymore, and you are serving on my ship.” However, it seemed a little over the top for Chief’s mild transgression… sometimes I wonder if we can’t have an episode without the Admiral giving a hard-hitting but inspirational speech to somebody. Eh.

On the Starbuck/Apollo reveal: Well. I guess it was pretty serious business that frakked up that. Man, those two didn’t think to hard about cheating on Anders and Dee. Anders, at least, I expect to be blindsided by Kara cheating on him (or at least he would have been surprised, before their marriage basically dissolved). But Dee definitely knew that there were unresolved feelings between Lee and Kara, not that that makes it better. It just reminds me of Kara and Lee’s conversation after Lee’s spacewalk, with Dee stealthily hanging out in the doorway. I really liked Dee after the documentary episode, because we got a better perspective on her background, and her little cues that she wasn’t entirely invested in her relationship with Billy. Her stuff with Lee, though, especially the Lee-Billy overlap, did not float my boat, and I did not see it ending well. That’s probably part of the reason I was so surprised that Dee and Lee got married, alongside Lee’s general obvious interest in Kara. (I wonder how they ended up married, and how Dee didn’t see the marriage as a Take-That to Kara and Anders…)

It’s interesting that marriage isn’t held up as some sacred happily ever after by the BSG writers. Actually, doesn’t that make Helo and Athena's the most successful marriage so far? Plus Chief and Cally, I guess. But the Tighs weren’t often in a good place and Bill Adama’s marriage fell apart, too, so unless I’m forgetting a bunch, the iffy marriages outweigh the successful ones.

Adama is using Chief as a stand in for all the people he feels he failed by letting them go on New Caprica. Tyrol was the first person, along with Cally, that he gave approval to live on the planet, which originally he didn't want to do. There's definitely a feeling of guilt on Adama's part, and being beaten by Tyrol was part of his self-imposed penance for letting everyone down. Ron Moore jokingly described it in the commentary as The Passion of the Adama.

4.5 Season 03 Episode 10: The Passage

Have you ever wondered what it was like to fly through baby stars?

This is the episode where BSG comes the closest to traditional science-fiction.

Most of BSG is about humans and humanity. It's all designed to feel very real– from the documentary-style shots of spaceship to familiar technological elements and simple dialogue lines delivered by exceptional actors.

But in this episode, we get something close to Star Trek. It poses a hypothetical problem that we don't face ourselves, something science-fictiony– traveling through a dense, irradiated star cluster. It gives Season Three the same gritty feeling we had when the fleet was still scrounging around for water or fuel in Season One.

They did a great job showing the hazard in this episode.. from the charred bbq'ed exterior on the Raptors to Kat's hair falling out. The badges are also a great invention as a measurement of radiation for the pilots and also a storytelling device.

The first time I watched the episode, it had a lot more gravity for me, because I thought the ships that were lost in the star cluster were full of people. I thought how much it would suck to lose contact with your guiding raptor and then burn to death in that cloud with your entire ship. But then I realized there were only skeleton crews on those ships and the rest were within the armor of Galactica, and subsequent rewatches had a little less impact.

Also, I loved the scene where Adama and Tigh started laughing over the stupid paper joke.

I got a chance to meet Luciana Carro, the actress who played Kat. I asked her what is was like when she found out she was being killed off. She begged and pleaded for RDM to change the plot but no luck.

In the commentary, RDM says that he didn't even get a chance to tell her she was going to be killed off, she found out as she was reading the script, which is a TV series actor's nightmare.

Man, when Starbuck finds out about Kat's past and shames her on it…. That was really uncalled for. Starbuck is being so harsh and spiteful, when everyone's past transgressions have been forgiven That is Starbuck though, she is a very hypocritical person. As annoying as she can be at times, that part of her character is fairly consistent throughout the series.

Humans and Cylons have weaknesses to different forms of radiation I think. Helo needed his anti-radiation shots as well as Starbuck on Caprica– the Cylons didn't, and Athena pretended to.

Totally agree with you on the scene with Kat and Starbuck. Carro did a great job… even the subtle groan of fear while Starbuck was threatening her.

I loved how she asked Adama if he wanted a daughter near the end too while in the hospital bed.

4.6 Season 03 Episode 14: The Woman King

In the commentary, RDM says that this episode was supposed to be a lead-in to a larger episode arc between the Sagittarons and Baltar's trial, but it was sidelined in the end.

For me the worst episodes of BSG are

- Black Market

- Hero

- The Woman King

"Black Market" sticks out because it appears in the otherwise-stellar 2nd season, right after two of the strongest episodes of the whole series. "Hero" sticks out because it makes Adama look like a huge bastard without really doing much to justify it from either his or the story's perspective.

"Hero" and "Black Market" have something important in common: they both try and introduce huge backstory elements to important characters that only serve to undermine those characters, and which are swiftly forgotten about (which sticks out in such a continuity-heavy show).

These two should serve as lessons to potential writers: don't introduce an earth-shaking bit of character history midway through the story unless you have a really good reason to do it, and make sure that you do your due diligence in making sure its effects are propagated properly. You could skip both "Black Market" and "Hero" (as I often have done when watching the series) without affecting the overall story at all; that's not a good sign for episodes that are basically meant to show what Bill and Lee believe to be the worst things they ever did.

On the other hand, "The Woman King" is bad to me because it doesn't really do anything or go anywhere. Helo's defining characteristic is his unswerving moral code, which he'll adhere to even at great personal cost; the episode is basically "Helo sticks up for the underdog like he always does, and then is eventually vindicated like he always is."

And unlike many Helo-centric stories, there's no ambiguity whatsoever; Dr. Robert might as well be twirling his mustache. The only grey area is Tigh, and even he rolls on Robert as soon as it becomes obvious what a dickhead he is. It would have been more interesting if Helo had to make a more substantive choice, such as compromising himself one way in order to serve a greater good, but that's something he does on several occasions anyways. They could also have had Tigh be involved more directly or even just be more reticent to turn on Robert; as it is he goes from ready to kick Helo's ass for so much as badmouthing him to immediately acting like he never knew the guy.

There are probably a few others that could be considered mediocre-to-bad in the mid-to-late third season, which I consider the low point of the series; this seems to be mostly because of the studio's insistence on a more episodic approach that just didn't work for BSG. Luckily they seemed to see the error of their ways.

It's so very predictable. It felt like every other episode on TV, like a procedural. We knew the guest star was the bad guy, we knew the good guy taking shit from everyone else was going to be right in the end, and, as a consequence, those people giving him shit for it come out looking horrible, too. Considering who the people were who were so down on Helo for suspecting that doctor, that's a bad move.

4.7 Season 03 Episode 18: The Son Also Rises

Sam Anders' flipping a coin and continually coming up with heads is reminiscent of the early moments of Tom Stoppard's play "Rosencrantz And Guildenstern Are Dead", in which Rosencrantz has the same result on a coin flip over a dozen times. This leads Guildenstern to comment "Consider - One: Probability is a factor which operates within natural forces. Two: Probability is not operating as a factor. Three: We are now held within un-, sub-, or supernatural forces." The moral is that two minor characters within a play (namely, Hamlet) have no control over their fate, and are condemned to carry out their role in the story regardless of their desperate attempts to change events.

According to Michael Angeli, Lampkin's first name, Romo, is from the first two letters of Ronald D. Moore's first and last names. Romo Lampkin was also initially conceived as a "55 year old Alan Dershowitz character."

The door code to Romo Lampkin's temporary quarters on Galactica is 1234.

The assassination of Baltar's lawyer was inspired by attacks on Saddam Hussein's defense team (Battlestar Galactica: The Official Companion Season Three).

The scene where Foster and Roslin reveal the last ship captain, in this case Admiral William Adama, was unscripted.

One part of this episode that I liked, that I haven't seen mentioned yet, was when Lee and Anders are in the memorial hallway. Lee starts to walk away, and Anders stops him and says, "Lee, I'll see you around." It shows to me that Anders has forgiven him for his history with Starbuck, and in the wake of her death he is just glad to have someone to share his grief. He is glad and comforted that he can be in the company of someone who loved Kara as much as he did.

4.8 Caprica Episode 18

If you watched this in the order proposed you are going to feel overwhelmed by the last minute or so of the episode.

I'll start discussing the things that didn't satisfy me from this serie. The first that comes to mind is the rushed finale. Bill shouldn't have that age at his brother's funeral and I wanted to explore the Lacey's part of the story more. We will never get an explanation of why Zoe is in the audience of the virtual church in which Clarice but that doesn't matter much. I wanted the producers to dive more into the colonies ideals, customs and traditions. In a similar way to the Taurons, for which we know so much now. We should have got more story on the Gemenon colony and how the STO had such a big presence there. The fact that the STO is so deep into the GDD and other places is incoherent with the first part of the story. V World in 2021 feels like a concept that has already been explored (in other works such as Dark City, Sword Art Online, Ready Player One, etc…) but I guess that I could have been amazed back in the day. The side of the story that interests Tamara is sort of hanging and New Cap City was cringey in some parts.

I am very happy that I watched the whole serie. The acting is very good, the scenes are good, the plot is good, the CGI awesome. They were able to have teenagers as key characters without lowering the bar for good drama. I felt a very strong connections to the more mature characters, expecially Joseph and Amanda. Every time they mentioned Joseph in the remaining S03 episodes I nodded knowing what they wanted to convey. I also like the fact that you get a lot of backstory but not so much that it can't remain a standalone serie. What was very interesting to see was the fact that instead of giving us just a good story that could be good enough to be a prequel to the Cylon War, maybe with some action here and there, the producers focused on exploring some moral and philosophical topics. On top of my mind the hypocrisy of religion and the gerarchy involved, brain in a vat topics, what it means to be human and the afterlife. Also they iterated on the topic of "It is not enough to merely survive, one has to be worthy of survival" but of course from the point of view of the Graystones, focusing on parenting and leadership at the same time.

I am sad that it was cancelled and there was a lot more to say. In a way what makes a good serie is the fact that the universe in which it is told is open ended and provides a lot of space to discuss even the same topics but from lots of different angles.

I am satisfied with my timing on this. I am sure that I should have started at the end of S03E17 instead of S03E18 but in any case I could go back to BSG without any spoiler, with the right amount of backstory at the right time, and most importantly, capable of picking up little clues in Caprica and in BSG, or so it seems for now.

On a minor important note, V World helps explain Cylon's phenomenon of "projections".

4.9 Season 03 Episode 20: Crossroads

All I am going to say is that I needed a chair with a deeper edge.

- It is also reaffirmed that none of the original seven is aware of the Final Five, as demonstrated by Sharon Valerii's lack of knowledge about Galen Tyrol's true nature during her relationship with him in Season 1 and the torture of Saul Tigh on New Caprica by the Cylons. In "Rapture," Number Three learns the identity of at least one of the final five and is heard to apologize; in retrospect, it's possible she was apologizing to Tigh for his torture.

- Starbuck's last words in the episode allude to "Maelstrom" as she is taking on the role of the Aurora idol that she gave to Adama before her "death." She claims that, like the idol placed on the model ship, she will be leading the way to Earth.

- The loss of Tigh's eye on New Caprica now has a kind of dark humor to it, as the centurions on both the original and re-imagined series are characterized by their single eyes.

- Tigh states that if he dies today, he will be remembered as a human officer of the fleet and a patriot. But if death for the Final Five is similar to that of the other humanoid Cylon models, if he dies he will be downloaded into a new body, surrounded by Cylons intending to manipulate him to their side or box his consciousness, and should he ever come in contact with those who knew him as a human, they would instantly regard him as a Cylon and therefore an enemy.

- After Jamie Bamber (Apollo) delivered his character's courtroom speech for the first take, the entire cast (who were sitting in the stands) and crew gave him a standing ovation.

- Consideration: a cheap TV serie would have gone with Lee snitching on the father and damaging their trust, even without changing the rest of the plot. BSG on the other hand decide to take the high road and propose a very deep, engaging and at the same time extremely difficult monologue. Instead of engaging the viewers by reflecting on a shared emotion (hubris, disdain, broken relationship with parents, division) the producers decided to express with new words the reason why the trial is so emotional and heart wrenching: "What system?", "This isn't a civilization, they are a group of refugees running for their lives pretending laws and customs apply to them as convenient as if they are on Earth" and all of the political ramifications of courts, judges and the defense system that are common in the whole series even before this two episode long climax.

On a personal note at this point of the show I hate Kara.

4.10 Season 04 Episode 03: The Ties That Bind

When Six's fleet is ambushed by Cavil's, the Orion constellation (as seen from Earth) can be seen in the background stars (approximately at 28:22 minutes into the episode). Whether this was intentional and signifies something is unknown. It may also indicate that the Galactica crew, as well as the Cylons, are getting closer to the Sol system. The Orion, as well as other familiar constellations would be seen more frequently in the episodes that follow.

4.11 Season 04 Episode 04: Escape Velocity

Distraught over the incident, Tyrol sits alone in Joe's Bar. Adama arrives and tries to console him over the death of Cally; Tyrol hallucinates and hears Adama call Cally a Cylon-lover who birthed a half-breed abomination, but really he had said that Cally was a good person.[1] Tyrol becomes enraged, insulting Cally and denouncing her as second-best. He says that the one who he really loved was Boomer, but she turned out to be a Cylon.

Galen Tyrol's insubordination that leads Admiral Adama to demote him may have been a deliberate act, conscious or unconscious, to maintain the safety of the ship. While not stated explicitly, Tyrol has been implied to have fears of working against the interest of the Fleet. This fear is almost certainly magnified when he forgets to swap out a burned out component for a new one on Racetrack's Raptor, which subsequently crashes. While his memory lapse may have been innocently brought on by the continuing stress of discovering himself to be a Cylon, the resulting subterfuge, and his wife's death, the experience of Sharon Valerii with her memory lapses, unconscious acts of sabotage, and the attempted murder of then Commander Adama, are probably on his mind. This is indicated during the tirade against Cally, Adama, and his life in general in Joe's bar. A demotion in disgrace and transfer could ensure the safety of the ship, without raising any unwanted questions as an official resignation probably would.

I like the device of having Saul and Tory playing good angel/bad angel to Tyrol as he contemplates what he should do in the wake of Cally's death. They both have two completely different viewpoints on the world post-discovery of being cylons, particularly Tory who I'm finding fascinating to watch. Her advice to Tyrol seems to be driven by her own ongoing experiences, which are to explore her surroundings as if she's never seen them before. Everything comes off as new to her. I loved Baltar's line to her after being on the receiving end of her "experimentation": I think I preferred it when cried.

"I like this service." It's sad watching Laura wind down. She knows she's not long and wants someone she cares for to know what she likes.

The old woman, Lilly, was played by Karen Austin, who we will see later the prequel series Caprica. Thought I'd make note of it as she is one of a few BSG alums to go on to have a role in that show. Did some digging in the wiki and I found out that Lillith (whose short form is Lilly) in Jewish mythology is among the first women to rebel against God. Here, Lilly is the first person we see reject the "one true god" in favor of the old.

This episode, along with the last few, really shows how far Roslin is willing to go these days in getting done what she thinks is good for the fleet. She says to Baltar, "There are some who say that when people get closer to their death, they just don't care about as much about rules and laws and conventional morality" and that she is no longer in any mood to indulge him, which are thoughts that could also be applied to the quorum. She's becoming more cutthroat of late. In addition to that Roslin's wig is strikingly reminiscent of Helena Cain's hairstyle in "Pegasus" and "Resurrection Ship, Parts I and II". This is a visual counterpoint to her increasing ruthlessness as she confronts her impending death.

4.12 Season 04 Episode 07: Guess What's Coming To Dinner

The Hybrid's prophecy that Kara Thrace is the "harbinger of death" takes on a new significance during Natalie's speech to the Quorum. Thrace begins to realize it may refer to the potential loss of immortality among the Cylons.

I love the tongue-in-check nature of the episode's title. For those unaware, the title of the episode is inspired by the movie Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, starring Spencer Tracy, Katherine Hepburn, and Sidney Poitier and is about interracial marriage in a time when it was still illegal in some states. The movie itself is pretty relevant to the episode since it's about the two races, human and cylon, co-mingling for the first time in a generation.

Two moments from the VFX team which I loved: The first is how the camera zooms in quickly when the Demetrius fails to jump away with the basestar. It reminds us of the "documentary" feel the show was trying to emulate and the shot itself feels like the cameraman was caught off guard, expecting the ship to jump away and then being surprised that it didn't. The second is seeing all the ships scramble to move out of the after the basestar jumps into the middle of the fleet. I love how the camera glides through the shot and we see a bunch of ships just narrowly avoid crashing into one of the basestar's outer spires.

Natalie's philosophy concerning the Cylons' need for mortality in order to value life parallels Zoe-A's statements to Clarice Willow when destroying the latter's apotheosis heaven decades earlier in "Apotheosis".

4.13 Season 04 Episode 04: Sine Qua Non

Ron Moore and the episodes writer, Michael Taylor, talk about Romo's cat in the commentary and even they admit the whole thing doesn't really make much sense. They talk about how the cat is a physical representation of Romo's demons from his life back on the colonies and how Romo is so plagued by the choice he made after the attack that he wants everyone to suffer as much as does. They say that he knows that Lee will be a good choice for the presidency and knows that he'll do good for the fleet, so he decides to kill Lee so that everyone will continue to suffer their lives as much suffers his own. However, they admit that they don't really succeed in communicating this to the audience and Ron calls the whole thing, particularly the invisible cat, a "bad idea" for which he chooses to take the blame.

4.14 Season 04 Episode 14: Blood On The Scales

Gaeta and Thigh are my favourite characters. Romantically Gaeta impersonifies a very vivid flame that burns with brightness and passion but is destined to run out of oxygen soon.

He is the most intelligent person of that age in the fleet and his accomplishment makes him sustain many responsabilities: in the fleet he has the unconditionate trust of Adama and in New Caprica he serves as the advisor of the president. His main accomplishments were saving the human civilization at the beginning of season 02 and during the stay in New Caprica.

In most of the exchanges with the other characters of the show Gaeta shows confidence, serenity, and no one ever questions his capabilities. Untils "The Face Of The Enemy" we don't get a glimpse of his humanity, except for the little dialogue with D'Anna in "Final Cut" (S02E08) where he shows the tiger tattoo while drinking and smoking. On the other hand given that most of the people of the fleet are very relaxed near him it is easy to understand that there is more to him than his skills.

His final actions that were central to this episode are well justified and to me they don't seem out of character. The pain he is enduring becomes more apparent when we get to see him injecting morpha. In "The Face Of The Enemy" his young age shows a lack of judgement in the people, he trusts. He is played by Eight in New Caprica and he becomes the scapegoat for Kara/Helo/Anders.

Since the abandonment of Earth the human population has been in a hopeless position of immobility and contempt. In this episode Gaeta wants to save humanity once again, but he entrusts once again the wrong person. In the end even if he dies his mission succeded: the crew had feel cohesion again and has found new motivations to endure the fight. In the dialogue with Baltar, when Felix asks Baltar to be remembered by the person that he really was, he was referring exactly to this.

Referring to the same dialogue, we must note that in the show there is a lot of dyadic development and in this scene Baltar-Gaeta comes to conclusion: Baltar acknowledges Gaeta, that by the way probally had a crush on him in the first season. Hopefully he will also understand how his cult is a danger to the development of civilization. Baltar's age and experience made him understand Gaeta's motivation better, probably since New Caprica, for which he is forgiven by Baltar many times.

Finally at first view a big fan of Gaeta such as me might remain puzzled by his hate for cylons. Since the beginning of season 04 we have seen a profound humanization of the entire cylon race. The reaction of Leoben to the discover of Kara's cadaver shows the very broad spectrum of emotions that they can feel. Using again his young age as justification I think it is easy to see how every interaction of Gaeta with the cylons has ended with despair and personal losses so it might be understandable that he harbors a profound hate for them.

4.15 The Plan

The Plan is not a particularly compelling piece of work on its own. In the context of the rest of the BSG story, it is interesting and useful, but with that context taken away the pacing is weird, the jumps through time are jarring, and the overall experience is kind of… boring. About 40% of The Plan also seems to be reused film from older episodes (which makes sense considering it is largely an extended flashback), but it doesn't help to keep you on the edge of your seat (it does however, make something of a decent "recap" before the end). Probably most egregiously, The Plan seems to lack a strong narrative structure and just kind of meanders through often very disparate events, loosely tied together by Cavil, who functions as the episode's main "protagonist". Absolutely absent are any significant moments of intense drama and tension, which are a hallmark of BSG, and is all the more unforgivable given the two-hour runtime.

I'll also get this right out of the way, as it is The Plan's weakest point: The Plan ostensibly attempts to explain the "And they have a plan" title card that preceeded most episodes, but does a pretty underwhelming job of doing so. "The plan" that is "revealed" is actually exactly what you'd guess and not new information: kill all the humans and make the Final Five realize that they were wrong (about humans, about Cylons, about god, and about Cavil). Neither of these points are spoilers because following episode 15, we already know this, and The Plan just reconfirms it. If you're hoping for some grand revelation of another surprise second layer of plan that had been going on all along, you'll be disappointed. The Plan is more about how Cavil reacts and adapts to the initial "success" of his original plan followed by several unexpected failures. To be sure, the Cylons did have several other plans going on concurrently with the main run of the show, like trying to get Sharon pregnant and then trying to steal her baby, and also the human breeding farms on Caprica. But the real focus of The Plan is on Cavil's plans.

But where The Plan is really strongest is not in explaining "the plan" or other plot minutiae, but in character development. Specifically with regards to:

- Cavil

- other Cylons: particularly Fours and Fives, but also Eights, Sixes, and Twos

- several of the Final Five: particularly the Chief, Tory, and Ellen

Secondarily, The Plan is also useful in filling in a ton of minor and not-so-minor unresolved plot points (I hesitate to say plot "holes") especially from the miniseries and first season and a half. Things like (but not limited to):

- Who told Adama there were only 12 models?

- How did all of the Final Five end up on the fleet?

- What were the various Cylons in the fleet doing during the first season?

- What was Boomer doing when she would "black out" and why did she fail to kill Adama?

- Who was Shelley Godfrey and how did she disappear?

But back to that character development: you're going into the last five episodes of the show, and that inevitably is going to include some kind of "final showdown" between the good guys and the bad guys. One of the problems with the show at this point is that most of the "bad guys" - the Ones (Cavil), the Fours (Simon), and the Fives (Doral) - have been generally underdeveloped.

Finishing episode 15, you've only just become aware of how Cavil was really the "big bad" of the whole show, manipulating most of the major events leading into the series. You've also only just discovered how important Ellen is to the story, and how far back the story of the Final Five goes. That's a lot to digest and yet not a lot of information with which to establish clarity and motivations.

The Plan works perfectly after episode 15 because it goes more in-depth into those very areas of the show that are lacking. You get to know way more about Cavil's objectives and how his mind works. You get to see more of Ellen and Anders and Tyrol and how they dealt with their life on the colonies and the aftermath of the Cylons attack. You also get to know Simon, and Doral to some extent, who are two of the most underdeveloped Cylons on the show.

The importance of that last point is often understated. It's often been said that a story is only as good as its villain, and the best thing that The Plan does is help flesh out and "humanize" its villains. You're probably yawning about learning more about Simon, and that's exactly the point: if you're yawning about one of the three last villains, then why would you care at all about their coming roles? You don't really care so much about the final confrontations with these villains when you don't really know who they are as characters and what their personalities and motivations are like. Conversely, going into the finale with The Plan under your belt makes that finale much more weighty and poignant and emotional.

And Cavil, as the main villain, benefits most from what is ultimately a Cavil-centric story. We learn more about how and why he started the second Cylon war to eliminate humanity. We learn more about why he betrayed the Final Five and put them to live on the Colonies. We learn more about his neurosis, his obsessions his weaknesses, and his character and morality. We also get a glimpse of an alternate version of Cavil and what he could have been - and this helps to "humanize" him and create a more believeable, more sympathetic, more tragic complex character. This is something that BSG excels at - not providing us with cartoonish, absolutely evil characters, or unimpeachable perfect "heroes". Everyone else is generally painted in shades of grey, but Cavil (and Simon) is lacking those shades without The Plan.

The Plan works well following episode 15 not just because it expands on many of the plot points and characters that just had game-changing revelations in said episode, but also because episode 15 is itself something of a self-contained informational episode. Following episode 15 is a great time to pause, breathe, learn more about the backstory of the plot, and ready yourself for the final leg of the race. In contrast, episodes 16 through 21 should all really be watched consecutively because they form the last story arc which barely begins with the final moments of episode 25. Any break in that progression would be awkward. (And watching The Plan at any point before episode 15 doesn't make sense because you really need that conversation between Ellen and Cavil to reveal how crucial both of them are to the overall plot.)

The alternative is that you watch The Plan after you finish the series, as so many here have recommended, and as so many of us did (because it was only released after the show finishes so we had no other choice), and this, in my opinion, would be a huge mistake. Remember my initial criticisms that The Plan is poorly paced, and not very exciting on its own. It's more of an interesting, informational episode than a good episode in its own right.

The thing is, heading now into the show finale, your interest is at an all-time high, and the main benefit of The Plan is that it will enhance your understanding of and enjoyment of the ending. Because of that, you'll more easily "suffer" through the story, while still being able to extract the later benefit. But if you watch The Plan after the story has already climaxed, eaten a sandwich, and gone to sleep, you'll be mostly bored, unimpressed at its lackluster storytelling, and missing out on the main purpose of that story.

Put simply, The Plan is terribly anti-climactic and its best features are wasted if viewed after the show is over. Once you've hit that emotional climax and release of the finale, your interest in a largely informational episode will be cool at best. The Plan is boring on its own but great at making the rest of the plot better. What's the point in watching it after the main plot is already finished? Have you ever watched a deleted scene to a movie you liked and thought, "wow, that was a great deleted scene, I liked it even better than the actual ending of the movie"? Probably not often. Have you ever watched a deleted scene and thought, "wow, I wish they had left that scene in the movie"? That feeling is the epitome of The Plan which is in essence a series of extended deleted scenes. They work really well when inserted into the main flow of the story, but they aren't absolutely necessary, and they're just kind of meh if watched separately.

Maybe the "plan" was: let the Five live with the humans where (according to him) they will run into all the bad sides of humanity. He thought, after they died, they would wake up with their real memories + the Colonial memories, and so would look at their time with the humans as a bad time. Because of whatever they may have experienced. When he was talking with Anders, he already realized that just by living with them, Anders was happy. His plan was already starting to fail right there and then. Basically it's like this. He wanted to put the Five in a situation he deems negative (living with humanity), but they are supposed to see the negative sides after they are removed from that situation. Right after removing them from that situation (the destruction of the colonies), they were supposed to look at that situation and see it for what it really is (to him): lies, hate, murder, whatever negative things humans can do. But they experienced so many good things and he didn't anticipate that because of his own jealousy and hate.

The two Cavil's featured here were referred to by the crew as F Cavil and C Cavil, with the letters standing for Fleet and Caprica respectively, so that's how I'll refer to them here. In addition to being Cavil heavy, another reason I liked this movie was because we got to see the cylons fleshed out a bit more, particularly the Simons, who I'd argue was probably the cylon model about which we knew least. We also get more confirmation how far down the cylon totem pole the Dorals are, so much so that they are doing what they consider to be centurion work.

- "Be prepared for some very sticky hugs." Right off the bat we're getting some great Cavil lines and he's got a lot of great darkly humorous lines in this. I loved his line to Shelly after telling her, "Very smart Six… Or maybe its the glasses."

- Love the callback to season one when Cavil introduces himself to Ellen as a 'Mysterious Stranger," which is what Ellen tells everyone when asked who rescued her back in "Tigh Me Up, Tigh Me down."

- Who would've guessed that the basestars are shaped that way so that they can pivot in order to become aerodynamic when entering an atmosphere. We never stop learning something new about the cylons.

- Love they whole Attack on the Colonies sequence. The editing, the music, the VFX, everything. It all flows so well together and made the attack seem as epic and catastrophic as it was. The nukes falling down, snapping open to reveal the nukes, then snapping open again to reveal even more was intense. I also loved finally seeing what we only heard about back in the miniseries. The cylon virus literally just turning off the battlestars, raptors, and vipers. Also, a particularly gruesome shot was of the centurions executing people still trapped in their cars on the highway.

- My second favorite cavil moment is from this. It's his first scene with Simon where all his anger and frustrations are unleashed. It's like he is pacing like a tiger when he is listing how all the cylons have let him down and goes to show how quickly he can go from sarcastic to frightening in a single moment. Again, Stockwell is so fascinating to watch, specifically in scenes like this.

- I loved the kiss between Tyrol and the woman. It never felt romantic to me, as Tyrol says, but more a symbol of acknowledgement of these two people commiserating over their situation's and how it bonds them in some way. In the commentary, writer Jane Espenson called it a non-romantic romance. The kiss is a kiss of understanding.

- Loved the juxtaposition of F Cavil killing the kid ("Friends can be dangerous things") and C Cavil not killing Kara. I think that the two are going through similar circumstances with their fellow cylons expressing the love they've developed for the humans, but clearly go in different directions when presented an opportunity to either embrace it or reject it. C Cavil sees the bigger picture and chooses peace whereas F Cavil also sees it, but chooses to literally kill the symbol of peace sitting next to him.

- The two Cavils meet up on Galactica, but its altered from how it went down in the season two finale. If you remember, F Cavil went along with truce and seemed to have prior knowledge of it but the retcon still leaves things a bit unclear. If F Cavil was no longer aware of the truce, what does he mean by the line "Unlike you, we can admit our mistakes"? C Cavil doesn't believe that the destruction of the colonies was a mistake, so I'm curous why they left that line in and yet changed so much else about the scene. I mean, even Laura is written out of the scene in this new version. I liked this movie overall, but this scene still doesn't make much sense to me.

- Cavil was always shown to be rude to the centurions, which we see again here even from a newly enlightened C Cavil, but I only just now realized its probably because Cavil is envious of the centurions. After he is what he desires most. To be a cold, hard, machine made of metal and wires and gears.

- "There's a 140 foot launch tube, we may die of our injuries before we get to the vacuum" Cavil is the worst shoulder to cry on, even to himself. I love it.

- That whole last scene in the launch tube between the Cavils is perfect. Stockwell plays the moment so well, even more impressive since he's acting against himself. I'm not really sure how to express how much I love that scene. It's so well written and acted and directed and shot and edited. And it ends with Cavil finally getting to feel the winds of a supernova flowing over him.

A few interesting things learned form the commentary:

- Frank Darabount was supposed to direct this and "Islanded in a Stream of Stars" but had to bow out, which is how Eddie was tasked with directing both.

- The rubble where Ellen is found is actually the hanger deck set after it was torn down.

- There were talks of doing a few more movies after this but they died down and it became that this would be the last time they shoot anything on the BSG set.

- When casting the boy who seeks refuge in Cavil's place, they intentionally wee looking for someone who looked like a young Dan Stockwell from The Boy With Green Hair.

4.16 Season 04 Episode 16: Deadlock

Not much to say except to make two clarifications:

- Why does Adama give guns to Baltar's flock? The question for Adama is to either allow a criminal gang to control the food supply or to allow Baltar's crazy cultists to control it. In addition to that Baltar's group, now armed to the teeth, would also serve as a civilian security force, which Adama figures is better than using centurions (deleted scene). In the end, Baltar's militia is the lesser of two evils.

- Why does Galen vote against remaining on the battlestar? He believe that cylons will never be accepted among humans and that now that he doesn't have any strong ties to Galactica's people (knowing that Nicky is not his son) he needs a fresh start and possibly the hope to get back with Boomer. In addition to that it could be discussed that he was nominated Chief again only because he is needed not because he is accepted again.

4.17 Season 04: Battlestar Galactica Finale (S04E17-18-19-20)

I wont play pretend to be a critico cinematografico. I'll just try to make an analysis of the important points of the whole show, or at least what impressed me and gave me something to think.

Let's start by saying that by setting the story in the past. The topos of the cyclic nature of the universe becomes stronger and we can imagine how Earth could become Kobol. The abandonment of some of the colonies technologies, the spaceships primarely, signifies the need for a reset and starting anew. This doesn't mean that technology was rejected alltogether and even if we have no indication of that the people of the colonies may have brought advancement to the natives. I believe it was well delivered.

Apart from the importance as a perfectly narrated conclusion to the story, the finale was important to me because it gave new light to two main points of the show.

I'll start with religion. In BSG we see people having beliefs that can be reconducted to panellenic religions, hindu's simbolism, egyptian gods (Hera/Isis), giudaism and christianity. It is suggested that by breaking up the remaining population of the colonies into different areas of the globe some these religion views may have broke down into what we came to now in current days. In the end religion had the same role that politics and societal constructions had in the whole story. It is a human construct that served as a ground reason for the war. The creators of the current cylon race were as flawed as any other humans and gave no reason for the cycle of creation and destruction. Finding a new home for the human race is not a moment of absolution for all the despair and sufference that the travel meant. Lastly the travel has a more mythological sense rather than religious: there are two figures, Galen and Felix, that impersonify Prometheus and of course there is an Eve. Kara by all means is Apollo. In the finale we come to understand that the central motor of the story is human nature for which religion as it is told can only offer symbolical and metaphorical interpretations. Hera didn't have a major meaning in the story apart from being a symbolical vessel for unification.I also believe that every character in the story (with the exception of Kara as we will see) walks along a path of self growth and maturity that never overshadows the inner human nature. In this context the predominant trait of each character shapes his personal journey.

The second point are the dyads which provide a frame to understand the characters of the story. I'll start with the most controversial: Galen.

Galen is a tragic hero that forms a dyad with Helo but shares his traits with Felix (the human part) and Tory (the cylon part). As Felix he rebels to his peers and fails to acts in betrayal by killing Tory. While Helo is the hero that always does the moral thing and can overcome his sense of refusal, Galen is consumed by contempt and every act by him meets a tragic fate. He is deceived by both races (Cally and Tory) and he gives up on both (Nicky and Tory, again). In the end he leaves the dyad and isolates as self punishment.

Sam is the another character that doesn't form a dyad. His humbleness is a proxy for his greater appreciation of universe and creation. As a person he acted as a tool for both races (resistance in Caprica, oracle of the five cylons, recovery of Hera).

Model Eight, which of course the dyad is made by Athena and Boomer, have the major trait of adherence to the uniform, from which most of their action revolves.

Gaius is probably the most complex character of the show. He is paired with Caprica Six, of which we come to understand didn't really love Saul, if we want to believe in love as the necessary ingredient for Cylon procreation. It is extremely important to understand that Gaius has been selfless and did what he did for Caprica out of love not pleasure nor self preservation. Both Gaius and Caprica Six burden the weight of scientific (cylon) and religious knowledge (Head Six) and act as the opposite force to mythology for the whole duration of the travel. The strongness in his character is evident by the burden of his experiences and his knowledge which would have driven many other people to madness and suicide. Finally, while Adama and Roslin are there show the most positive traits of human nature and the qualities to which strive for, Gaius and Caprica are there to show our flaws. In a way Gaius was absolved by the trail, even though it didn't account for giving the nuke to a Six. It must also be noted that when other characters such as Adama and Starbuck takes bets on some big action they always turn out well, Gaius the opposite and often his choices turns out mostly wrong but with a possible solution. In end always the other side of the coin.

Regarding the angels, we have Head Six and Head Baltar that form a dyad, and Kara which doesn't. Head Six and Head Baltar shows us the true form of the faithful belief, intended as the perpertual cycle of creation and destruction, shaped as a complex system that will eventually surprise us. God, as symbolized by the final dialogue, is not something to which we can give a name. Kara doesn't embark in a path of growth and is the most infelice character because she doesn't provide any reflection of the positive human nature and in the end her only meaning is to input a series of number in a pad. The numbers which on an unrelated note where given to her by what we know is her father, the pianist.

In the last scene, are “Six” and “Baltar” angels or demons?

Moore: I think they’re both. We never try to name exactly what the “Head” characters are—we called them “Head Baltar” and “Head Six” all throughout the show, internally. We never really looked at them as angels or demons because they seemed to periodically say evil things and good things, they tended to save people and they tended to damn people. There was this sense that they worked in service of something else. You could say “a higher power” or you could say “another power,” [but] they were in service to something else that was guiding and helping, sometimes obstructing, and sometimes tempting the people on the show. The idea at the very end was that whatever they are in service to continues and is eternal and is always around. And they too are still around…and with all of us who are the children of Hera. They continue to walk among us and watch, and at some point they may or may not intercede at a key moment.

I now give some reviews by other people. They are way more focused on details than me. While I only complain about the error regarding Hera's blood (come on, it should have been an hint and it turned out to be wrong) I don't agree with the criticism of the Deus Ex Machina and I don't want to focus the entire judgment of the show on some hints given in the last three minutes. Yes, the 150000 years thing is out of place but it is such a wide gap that we can take the liberty of filling out the gaps with our imagination and even slightly adjust what it has been an extremely wonderful science fiction story.

One last clarification about the Cylon God. I believe the Cylon God to be a fallen Lord of Kobol and it is a direct analog to Yahweh. Elosha states that the exodus from Kobol was precipitated when "one jealous god began to desire that he be elevated above all the other gods, and the war on Kobol began." This god was eventually separated from the others. This figure may be related to or identical with "the one whose name cannot be spoken", whose temple is discovered on the algae planet ("The Eye of Jupiter"). While humanoid Cylons show a strict, firm belief in a monotheistic God, referring to the Lords of Kobol as "false idols," a connection between the Cylon God and the Lords of Kobol may exist. During the Cylon occupation of New Caprica, an oracle tells Number Three (who has a dream of the oracle's tent and of holding the believed-dead hybrid child Hera") that she has a message from the one that Number Three worships ("Exodus, Part I"). This poses the question how an oracle of the Lords of Kobol is able to hear the messages of the Cylon God. The Temple of Five, which a Number Three uses to visualize the identities of the Final Five", was not built for the Cylons (who were not created until 4,000 years later) but for humans. The Temple, according to the Sacred Scrolls, was built for five priests who worshiped "The One Whose Name Cannot Be Spoken". It is not clear if this was the spurned "jealous god" or another fallen member of the Lords of Kobol. This is not in conflict from what we see in New Caprica, where a small minority of monotheistic humans existed on the Twelve Colonies before the Fall. Their religion was looked upon as dangerous and heretical by the majority of Colonial society and most of them were forced to hide their beliefs. The kernel of Zoe-R's identity contained in the Cylons' fundamental programming which Lacy exploited also made them predisposed to monotheism. Ironically, the Cylon marines' killing of monotheist human terrorists to protect the thousands of polytheist humans at Atlas Arena (coincidental to Lacy's coup) ingratiated the Cylons with humanity and was the catalyst for their much more rapid popularity and sales than inventor Daniel Graystone had anticipated ("Apotheosis"). Sister Clarice Willow proselytizing to her Cylon congregation.

Sister Clarice Willow evaded capture for her orchestration of the failed arena bombing. She eventually discovered the Cylons' monotheistic instincts and established a Cylon congregation in V-World where myriad domestic, industrial, and military Cylon models came to hear her sermons. Opening with the rhetorical question, "Are you alive?" Clarice preached that Cylons are every bit as much God's children as humans are. Blessed Mother Lacy granted Clarice an audience at her see on Gemenon to discuss Clarice's proposal for divine recognition of the "differently sentient" - the Cylon race ("Apotheosis"). Despite being human herself, Clarice encouraged her Cylon flock to rebel against their human masters.

The Final Five traveled from the thirteenth world (Original Earth) to warn the humans of the other twelve worlds not to make a robotic slave race which would inevitably rebel as their own had done ("Sometimes a Great Notion", "No Exit"). They arrived more than twelve years too late to avert precisely the war they had prophesied ("No Exit"). While they could not prevent the war, they could cause peace. They agreed to give the Centurions the technology they were themselves trying in vain to develop: the ability to create biological Cylons, along with the inherently interrelated resurrection capability, on the condition of an immediate Cylon withdrawal and armistice ("Razor Flashbacks", "No Exit"). The monotheism of the Centurions was incorporated into the programming of their humanoid "children."

Immediately before igniting the holocaust, a Six quotes from Sister Clarice Willow's sermons decades earlier, asking the human Armistice Officer, "Are you alive?" (Miniseries, Night 1, "Apotheosis") The Cylon religion's lineage can also be seen during the Cylon Civil War, at a Cylon funerary service that takes place on the Battlestar Galactica, where the usage of ornaments and amulets in the form of the infinity symbol can be observed ("Islanded in a Stream of Stars").

The Cylon God and the Lords of Kobol have an "overlapping" existence that is confusing to both Colonial and Cylon sides. Both sides appear to be guided to conflict (and, in rare instances, cooperation) through events that appear pre-destined. The story arc of finding the Arrow of Apollo involves the hunt for the Tomb of Athena by the Colonials. According to the Sacred Scrolls, the humans will be aided by a "minor demon." The cooperative Sharon Valerii copy assists the group in finding the tomb.

Regarding personal theories, it is possible to tone down the most religious sides of BSG by thinking that everybody is an unaware cylon. This means that oracles and visions are explained by the ability to project and that agents of faith such as Kara and the head couple Head Six and Head Baltar may be very advanced cylon models that achieved trascendence, possibly in the way Cavil imagined. This is a stretch because there are three instances in which humans can discriminate between a cylon and a human:

- Baltar's detector

- Hera's blood

- when they analize the remainings on earth

but in all honesty this only means that there are differences between models, and this is something that we already know. To me this theory is important because it would show that the most important gift the cylon would give to Earth's primitive humans are genetic advancement in the form of hybridation with them, rather than technological advancements. We know how important and advanced are genetic and organic technologies for Cylons and this would also explain the big history gap of 150000 years.